Navigating Complexity: Why Business Transition Is So Costly and Error-Prone

In the past few months, we’ve had almost 100 conversations with CEOs and board members lamenting their frustration with slow growth and the difficulties of transitioning their businesses to the new realities of driving profitable top-line growth. They are on their third or fourth sales leader in as many years – but none has been able to accelerate organic revenue growth sustainably. Their sales of a flagship product, once robust, are inexplicably waning. They are pouring resources into new geographies or customer segments, but they aren’t growing as expected. Why do they want to know, are they experiencing so much difficulty with driving top-line growth? Why aren’t their actions driving the expected results?

When we dig in to find out what’s going on, we typically find that while the specifics vary by company, the overarching problem is almost always the same: Leaders are making decisions and taking action for the wrong phase and circumstances of their company’s development.

With their heads deep into the day-to-day, quarter-to-quarter running of the company, many CEOs miss seeing the gradual, subtle shift of a business into a new phase and the challenges of driving growth. That’s a problem because the actions that work when a company is on the upward slope of growth, being pulled along by market demand, do not work when a company has reached the apex or is on the downward slope of the curve when demand needs to be driven. On the whole, the CEOs who express the kinds of frustrations mentioned above are making decisions independent of consideration about where their companies are positioned on the lifecycle curve and the complexities and challenges associated with that market position.

When business leaders lack a deep, fact-based, understanding of the circumstances they are facing, it creates a perfect storm for value loss, multiple attempts at change, and hemorrhaging of resources and time.

Six Lifecycle Stages

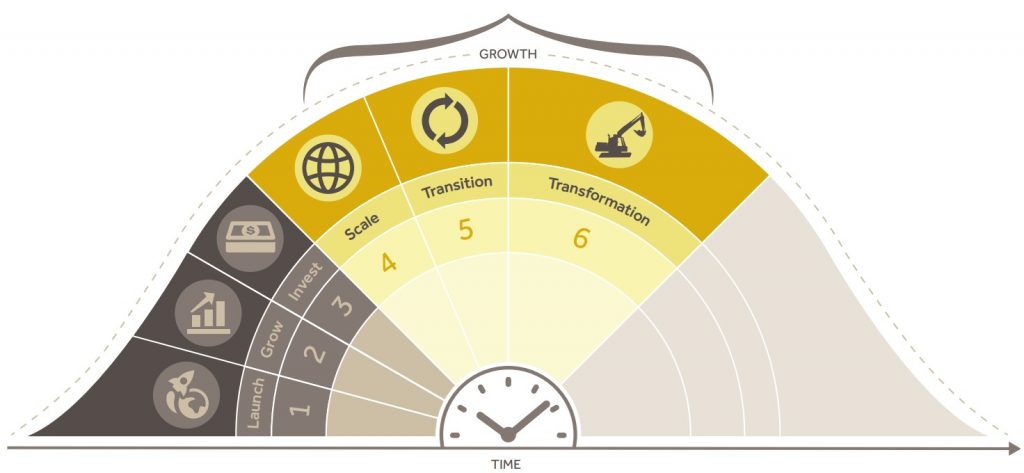

By way of background, there are six lifecycle stages companies move through as they grow and mature.

Each of these stages involves a major change in strategy and focus and requires different leadership styles and organizational talent:

STAGE 1 (Launch): This is basically an idea and a market. It’s the proverbial “couple of people in a garage” likely hunched over a computer, creating a product or a “killer app”.

STAGE 2 (Grow): From the initial launch, these companies begin to acquire customers, slowly at first but at an increasing rate, and can validate the demand of their offering more broadly. This stage is about bringing in customers as quickly as possible and growing at any cost.

STAGE 3 (Invest): Stage 3 companies have maxed out their financial resources as well as friends and family investment and need to turn to more formal sources of capital. Pretty quickly they must show they can grow beyond their initial product, establish a Go- To-Market model, and create sustained profitability. It’s here that companies must apply business discipline and continue to maximize growth.

STAGE 4 (Scale): Stage 1-3 companies do pretty much one thing which is serving the demand that exists for their offering; in Stage 4, they must expand the market by

identifying new segments and new products to maximize customer potential (“share of wallet”) and acquire new customers (“new logos”) to drive sustained and predictable growth and profitability. For example, Uber, which previously only drove people from A to B, added Uber Eats, Uber for Business, and JUMP Bikes.

STAGE 5 (Transitions 1-n): This is typically the stage where a company is approaching the apex of the normal distribution. It’s where a company’s growth starts to slow, and in some cases, they start to lose or barely maintain market share in some of their markets or segments. It’s where they notice they are growing in single digits instead of double digits and where they must start “pushing” their product rather than simply responding to the “pull” of the market. It is in Stage 5 that companies must re-think their go-to-market models, coverage of their addressable market, re-tool their approach to channels, prioritize segments and geographies and take a candid look at the talent and incentives they have in all customer-facing roles including sales.

STAGE 6 (Transformation): As companies get further into the back side of the curve, they must fundamentally re-think and change their business model and skills, tools, and capitalization. They may decide to adopt a “shrink to grow” mentality, reducing complexity in order to be successful going forward. CEOs here must be able to move resources nimbly, shedding what’s not working (or what’s hanging on because it’s underperforming) and innovating new products, solutions, and customer-driven approaches.

Armed with this fundamental understanding, every business leader needs to ask themselves two questions:

- Where is my company positioned on the maturity curve? This is the starting point. Are you on the left side of the curve or the right side? If you’re on the right but you are taking actions appropriate for the left, you’ll wind up burning through cash as you attempt to stimulate growth via a “pull” market when in reality your product has become commoditized and you need to “push.” If the lifecycle curve were a clock, the complexities of growing a business are especially pronounced in the 10-2 range – and they are markedly different for companies in the 10-12 versus the 12-2 segments.

- What are the complexities and challenges I need to deal with and do I have the talent necessary to make the critical changes and return to growth? Someone who is successful on the left side of the curve when a company is in hyper-growth mode is unlikely to be successful on the right side. On the left, you need people who can expand and scale, who can produce and distribute goods to meet demand; on the right, you need people who can create demand with a global, strategic approach to sales. The right side of the curve involves managing the complexity of optimizing profits in the core while managing the “pull” of growth in new products, segments and geographies.

The Sales Leader Conundrum

Against the backdrop of understanding complexity and lifecycle position, let’s look at one of the most common frustrations of CEOs: the revolving door of sales leaders. We hear all the time comments like, “We are on our third head of sales in five years – what’s going on? Why can’t I find someone to effect real impact on the top line?”

In nearly every one of these cases, we find the CEO is hiring as if the company is in a steady state with the new head of sales looking almost exactly like the previous one and coming in with a sales playbook and go-to-market model from the past. Not surprisingly, they wind up being equally disappointing. When business leaders start from an understanding of the changing nature of the market, current organizational maturity, and the nuances of the company going forward, and seek to bring in a sales leader who is a fit for the circumstances – a leader who is agile and a competent change management leader – they achieve the desired results without multiple attempts at getting there.

Keep in mind that “fit for circumstance” is about more than just the lifecycle phase. If you look at stages 5 and 6 – Transition and Transformation – there are issues that occur within these phases which require different sales leader profiles. For instance, a product-based transition/transformation suggests the need for new product development and new-product commercialization skills – a very different skill set than what’s required in a channel transition or a pricing transformation. You can begin to see why, without an understanding of the specific skills needed in a leader for the specific circumstances and lifecycle position of a company, CEOs can easily move through multiple heads of sales in a few years without finding the right fit.

Related to this scenario is the head of sales who has been with the same company for four, five, or more years and, although once highly effective, is no longer producing the same kinds of results. Often, CEOs will hang onto these formerly successful sales leaders in the hopes that, given enough time, they’ll be able to replicate past success. Or they’ll hang onto someone because she has a long history with the company and everyone likes her. Or because he has established so many long-standing relationships that the CEO fears replacing him will cause a loss of customers or top reps. This is just as dangerous to a company – in some ways, more so – as the revolving sales leader. But the problems are both rooted in the same cause: while ideal for an earlier phase and challenges of the company’s development, the leader is not suited for the organization considering the complexities it is facing today.

We often see this play out in tech companies that shift to a new delivery and revenue model during the sales leader’s tenure. The head of sales is working hard to do what he has done historically because it worked well historically, but the company has evolved from selling software to a cloud-based solution – a completely different sale with a different sales process, sales model, revenue model, and compensation structure. Everything has changed – except the skills of the sales leader.

We once worked with a technology company that had two senior sales leaders who had not closed any new logos in two years. They were doing well but only on the backs of existing customers. Both had been with the company since its inception and, in the minds of company leadership, were therefore untouchable fixtures. But both of them were stuck in Stage 2 while the business had moved on into the critical 10-2 segment of development. When these leaders helped start the company, there was enormous demand and their job was simply to meet it; they had no skills to lead a large sales force dealing with the complexities of growth in stages 4-6,

creating a kind of tug-of-war as the business tried to move forward but the sales leaders held it back. Once the CEO understood the damage and inertia these two leaders were unwittingly creating in the business, he exited one of them, moved the other to an account management role within the company, and brought in a new sales leader whose skills matched the needs of the organization. These actions unblocked the revenue growth, returning 4x revenue within 36 months.

This problem can affect talent all the way through the sales force. Like the company above, we recently worked with a business whose entire sales force had never “sold” anything. Facing rapid growth through the early stages of development, sales reps simply answered the phone and took orders or completely relied on an overlay sales team because they were first to market and the best at what they did. As the product portfolio grew, they became coordinators vs. sellers.

After some years, the company found itself in Stage 5 with 3-4 solid competitors, waning market share – and no idea how to sell. They wound up replacing about three-quarters of the sales force because their skills were in passive order-taking, not hunting to build demand, drive sales and increase market share.

Beyond Talent

Obviously, the problems associated with making decisions without a clear understanding of a company’s position on the lifecycle curve extend beyond leadership and talent to encompass every major aspect of growth and development. Once you move into the 10-to-2 o’clock segment of the lifecycle curve, the complexities of running a business multiply exponentially. From a small, one- or two-office organization reacting to the “pull” of the market where demand is great, and the big question is whether you have enough resources to meet it, businesses in the later phases of development face much more difficult questions. How do I manage the complexity of selling our growing product/solution portfolio? What’s the right channel mix? How do I sell against copycat competitors leveraging technology to achieve a cost advantage? How do I leverage pricing for maximum margins? How do I shift from operating in a “pull” market to succeeding in a “push” environment? When smart CEOs tell us, “I’ve re-done my channel three times in the last four years and I’m still not getting the ROI I expected!” we know that caught up in the day-to-day running of the business, they have likely missed the fact that their company has shifted to a new position on the clock and in the market.

Those shifts can happen subtly. Often, sales start to wane in some segments while others are still performing well. On the left side of the curve, it’s not uncommon to see a company with, say, five or six products/solutions/segments that are doing well and making up for three lagging ones. The CEO is spending a lot of time and money trying to fix the laggards because she’s accustomed to the strong demand of a “pull” market. But the circumstances have changed and before she knows it, the five or six that were doing well are now mediocre and leadership is trying to plug eight holes instead of three when perhaps the right decision was to wind down or divest the laggards, support the strong performers and put more resources into a small but promising part of the business that is growing at two to three times the rate of all other aspects of the business. These are the complexities of the “push” side of the curve. Companies must maximize the profitability of the core while fueling the growth of the new – those products or business units in “pull” mode. The challenge is that the core, being larger and more dominant, can smother the upside of the new. Balancing the two impacts structure, talent, investment and takes a holistic perspective and an outside-in market vision.

Without that holistic understanding, companies usually lean towards fixing what’s in the rearview mirror – a product line, a geographic area, a sales leader – but that may no longer be appropriate for the company and the market. One CEO we worked with was concerned about the high number of open requisitions in several geographies that, despite strong growth in the past, were now lagging. His company was pouring resources into these markets in an effort to revitalize them and he was concerned they were wasting those resources. He was right. An analysis of these markets revealed they were saturated and highly competitive; the company had more than 70% market share and further growth opportunities were limited. Armed with this understanding, the CEO redirected investment to markets with significant growth opportunities.

Is your business in transition? Do you know exactly where you are positioned on the lifecycle continuum, what actions and talent you need to grow going forward – and how to get it right the first time? Or are you, like many organizations, navigating in the rearview mirror, expecting the topography behind you to help you move through the landscape out the windshield? It won’t.

Only by gaining a clear understanding of your company’s lifecycle stage and the details of the challenges and complexities the company is facing can business leaders successfully navigate complex business model transitions – the first time – and expertly position their companies for the next stage of growth, creating significant value and gaining exceptional market advantage. The result is a collective buy-in to the vision and transformational journey and a positive cultural shift that is sustainable and drives long-term, predictable growth.