A Roadmap for Growth Outside the Core: 3 Steps to Successfully Exploiting Market Adjacencies

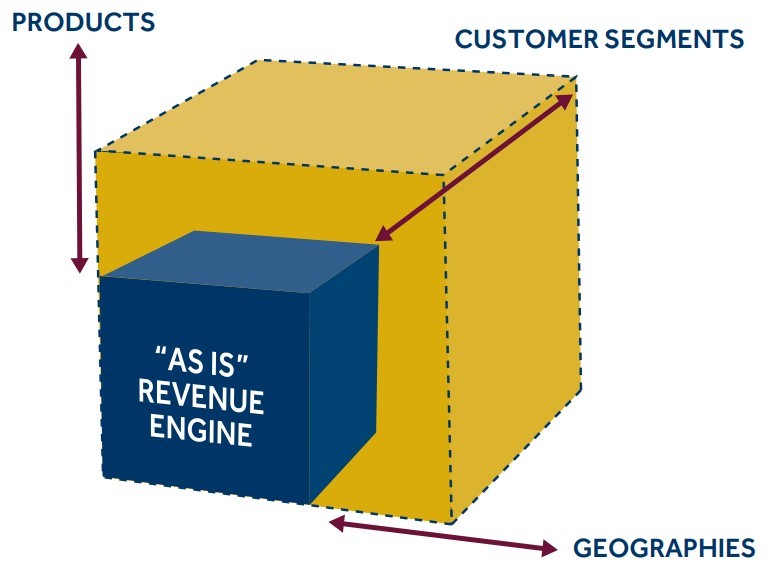

As companies around the globe seek acceleration of their growth rates, focusing on the core business “revenue engine” is as critical as ever. Tuning up or overhauling pricing strategies, sales, and marketing capabilities, or go-to-market approaches can make a meaningful impact on growth. However, many companies aspire to generate growth beyond that which can be achieved through those means. In some cases, organizations are already leading their industries in revenue growth rates, and their “engine” is already firing on most, if not all, cylinders. In other cases, company size, competitive positioning, or declining market conditions require more than sales and marketing-related improvements to achieve growth aspirations. Regardless of the reasons, for many companies, desired growth can only be realized by expanding into new markets, whether they be new products, services, customer segments, geographies, or entirely new businesses.

Once upon a time, large conglomerates such as ITT, RJR Nabisco, Tyco, and Sears Roebuck would build or acquire businesses in a variety of unrelated industries. For multiple reasons, the conglomerate business model didn’t last. Today, successful expansion into new markets requires sound strategic and financial rationale, such as a common customer base, sales and marketing synergies, manufacturing consolidation, and the ability to leverage technical capabilities. Because there are one or more points of commonality between the current business and areas of expansion, these new markets are often called adjacencies.

Determining which adjacencies make the most sense and developing a strategy for entering these new markets is a complicated and risky undertaking. Companies that have identified extension beyond the core as a means to accelerate revenue growth often do not have the resident knowledge, institutional capabilities, and/or industry relationships needed to be successful. Unfortunately, some do not acknowledge those shortcomings prior to making an acquisition or funding new organic initiatives outside of their core.

As a consequence, these companies do not realize the full potential of entering a new market, or worse, disrupt their core customer base and eventually destroy shareholder value. Other companies appreciate the magnitude of the effort required but never seem able to allocate the necessary resources to do the work, given the day-to-day challenges of running a business. Regardless of the reason, significant growth opportunities are often left unrealized.

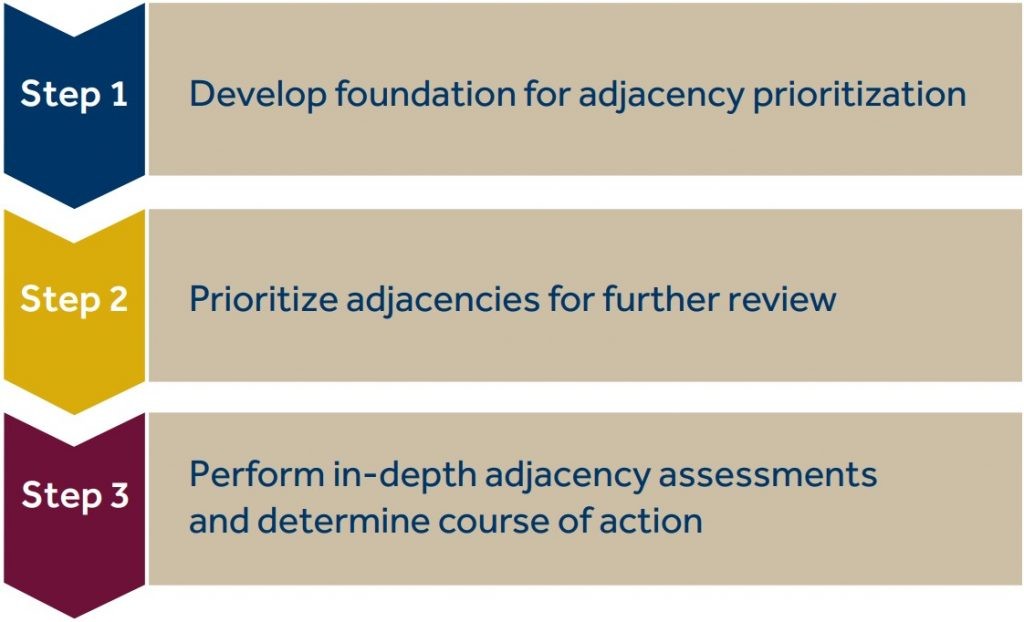

Through our work helping dozens of companies chart paths to growth through new market entry, we have developed a three-step approach to adjacency assessment and prioritization that allows for a large number of potentially attractive adjacencies to be quickly identified, prioritized, and narrowed down to one or more that a company should pursue:

Step 1: Develop a foundation for adjacency prioritization

At the beginning of any adjacency assessment, companies are well served to (i) define the objectives for any ultimate expansion, (ii) document the company’s truly unique assets and capabilities, and (iii) develop a list of strategic and financial criteria that will be used to assess adjacent markets. This “foundation building” should include all key constituents in the company, including line executives of existing core businesses.

This consensus-driven approach is important for two reasons. First, by aligning key stakeholders on the reasons for, and urgency of, an expansion into new markets, a company will mitigate the risk that a sound strategy is not accepted by the leaders who need to execute it. Second, with a common vision for what would qualify as an acceptable adjacency, the organization will be a lot more efficient with the resources used to conduct the scanning effort.

Failure to gain consensus early creates confusion and decision paralysis later on in the effort. For example, the CEO of one multinational manufactured products company charged an internal team with scanning adjacent markets and determining which ones to pursue. However, she did not create a clear “case for change” in the eyes of her lieutenants. Consequently, each time the internal team presented a recommendation about a particular adjacency, senior leaders could not agree on whether the expansion would be a wise or unwise move for the company.

| Key Outputs from Step 1: • Definition of strategic objectives to achieve by extending beyond the core • Identification of truly unique organizational capabilities that can be leveraged in an expansion into another sector • Strategic and financial criteria to guide the assessment and prioritization of adjacencies • Preliminary hypotheses on attractive adjacencies |

In contrast, a medical device company with which we recently worked took a much more methodical approach that resulted in up-front consensus. The management team began with a working session during which senior stakeholders documented key issues facing the core business, developed a set of objectives regarding what they wanted to accomplish with the expansion effort and assessed what capabilities they had that were unique and could be leveraged to create a competitive advantage. In this case, they decided that one of their strongest assets was the customer relationships and loyalty that the company enjoyed. At the same time, they determined that while the core business growth rate was acceptable, they needed to improve sales representative productivity (i.e., annual sales per rep) to improve their EBITDA margins. With common agreement about the capabilities to leverage and the objective of the adjacency exercise, they had successfully established boundaries around which each member of senior management could rally.

As mentioned above, along with gaining alignment on the objectives for any expansion effort and the company’s unique capabilities, defining a set of financial and strategic criteria is paramount for success in the effort. These criteria should be clear, specific, and as objective as possible. For example, financial criteria might include minimum market growth rates and gross margins; strategic criteria might include competitive concentration and relative commoditization or differentiation of products or services sold by incumbents. While there is a qualitative nature to assessing strategic criteria, companies should still choose criteria that are straightforward to assess. Below is an example of financial and strategic dimensions that might be the basis for the screening criteria used in an adjacency scanning effort.

- 5-year growth rate

- Industry profit margins

- Pricing/reimbursement

- Competitive concentration

- Technical risk

- Capital intensity

- Regulatory environment

The final foundational element for the adjacency scan is the generation of hypotheses about attractive adjacencies. Agreeing on a list of industry sectors that are candidates for evaluation provides focus and direction for the effort. We find that 7-10 adjacencies are a good number with which to begin this effort as it allows companies to cast a wide net and still complete the scanning effort in a reasonable amount of time. As an aside, it is sometimes the case that an adjacency ultimately pursued wasn’t on the original list of hypotheses. In these instances, the initial round of assessments helps companies refine their objectives and screening criteria, and leads to insights about what sectors are better fits for expansion efforts.

Step 2: Prioritize adjacencies for further review

With a list of potentially attractive adjacencies in hand, the next step is to develop a fact base that can be used to screen each adjacency using the filtering criteria developed in Step 1. The fact base collected during Step 2 should not be comprehensive; rather, it just needs to provide enough information to rank and prioritize each adjacency relative to the others based on the key screening criteria. This is an important mindset. Without it, companies will spend far too much time and money analyzing adjacencies that don’t warrant the investment.

In our experience, much of the fact base necessary to do this filtering is available in the public domain and collected via secondary research (whether for purchase or freely available) through sources such as:

- Professional research reports

- News articles

- Trade magazines

- Trade association websites

- SEC Filings

- Earnings call transcripts

- Internet forums (e.g., social media, chat rooms)

- Company websites

- Job postings/resume boards

Many of the above sources are obvious and intuitive, but the last item on the list is worth a special mention. We find that information communicated in job postings, and especially in resumes and profiles on social media (e.g., LinkedIn), often reveals important data elements. For example, on a recent engagement, we triangulated the size of a niche product category using the resume of the market-leading company’s former head of sales. Because of the relatively small market, competitors did not report segment sales in their SEC filings and there were no published research reports. Based on our primary research and survey data, we felt comfortable with the insights we’d developed about relative market shares.

We used a couple of different approaches to estimate the aggregate size but wanted further validation. The posted resume we found disclosed the prior year’s revenues for this market leader, allowing us to develop a third estimate for the market size and increase our level of confidence in the range on which we ultimately settled. In addition to secondary research, we find it helpful to augment the fact base through selected primary research such as phone interviews of market participants. While there isn’t time to conduct extensive primary research (we save that for Step 3), a handful of well-placed calls will provide additional helpful perspectives.

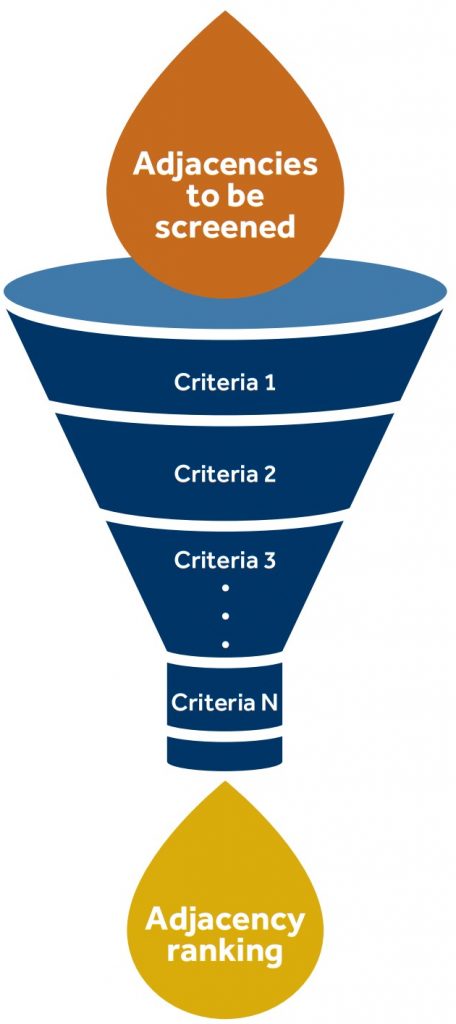

Once fact bases are developed, we filter each adjacency through the screening criteria developed during Step 1, as shown below.

Potential screening criteria:

- Long-term market growth >x%

- Profit margins >y%

- Size/scale of investment required

- Neutral to the attractive pricing environment

- Acceptable level of competitive concentration

- Acceptable level of technical risk

- Limited capital intensity

- Opportunities and/or risks created by industry trends

In the conduct of these screening activities, the scoring of adjacencies on each criterion can be done using any convention that the user prefers – 1 through 10, green/yellow/red, etc. – as long as it enables prioritization of the multiple adjacencies. An example of the screening approach and output from this prioritization task is shown below.

The objective of this step is to reduce the number of potential adjacencies to a manageable number of market sectors for a “deep-dive” assessment. As such, the scoring needs to result in enough differentiation between the adjacencies to allow for an informed decision about which sectors warrant this additional work. In the above example, adjacencies A, B, and C may be chosen for advancement to Step 3. Importantly, successfully completing Step 2 requires comfort with ambiguity and a willingness to rule in or rule out adjacencies based on imperfect information. Failure to do so in a timely manner can result in many expended resources with no impact. For example, a middle-market business services firm had been evaluating a number of industry verticals for which they might introduce a service offering. While the company had collected a reasonable amount of information about each sector, they found themselves lost in “analysis paralysis” for over a year, striving to answer every conceivable question about each adjacency. Being spread so thinly across a dozen potentially attractive sectors, the company made no progress in the pursuit of any single adjacency, despite having identified growth beyond the core as a strategic priority.

Step 3: Perform in-depth adjacency assessments and determine the course of action

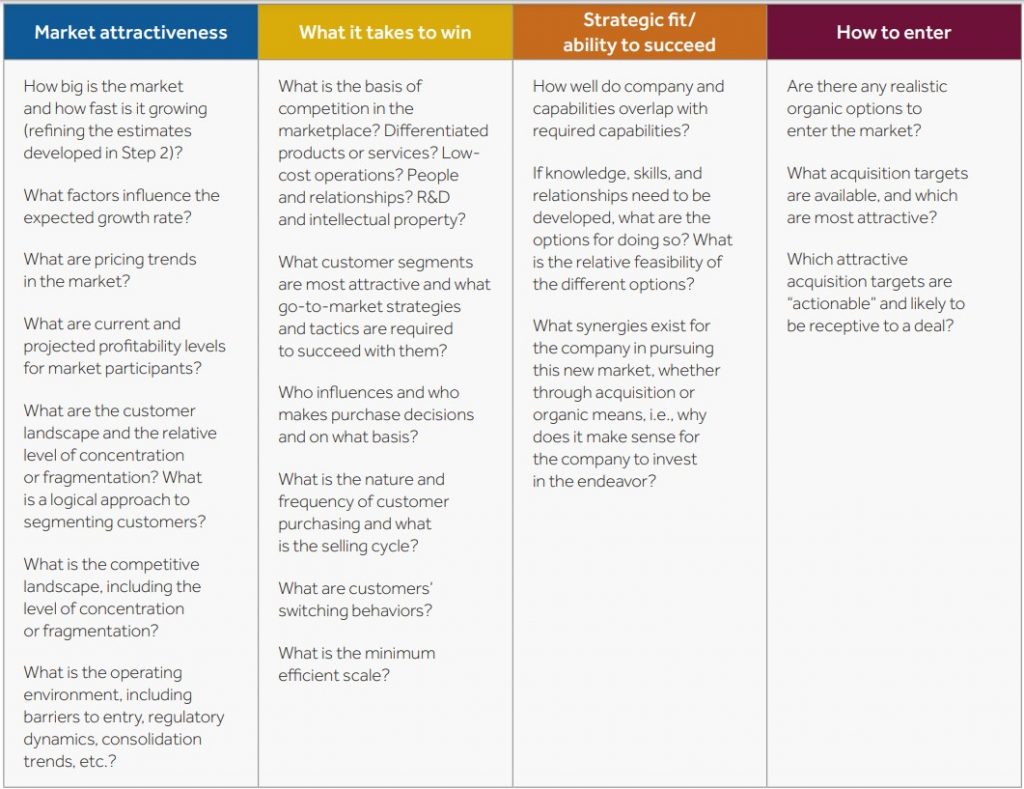

For each of the top-priority adjacencies, an in-depth assessment should be completed, and more insightful perspectives about market attractiveness and strategic fit should be developed. As part of the in-depth assessments, it is important to address the following questions:

While secondary research continues to be an important part of an in-depth adjacency assessment, the information needed to answer these questions won’t ever be found online or in a purchased research report. In addition to conducting more exhaustive secondary research than was done in Step 2, a concerted primary research effort is required. At Blue Ridge Partners, we use a methodology we call Nine Voices of the Market®. Everyone has heard of “the voice of the customer,” but eight other voices can be valuable in generating insightful perspectives about the market and its participants. Industry executives, marketing and sales representatives of companies competing in a given adjacency, and other experts provide important inputs to the adjacency assessment, augmenting what can be gained through customer conversations alone.

For example, we recently helped a client evaluate an adjacency that had fundamentally different dynamics and buyer values across the three primary market segments. Although a detailed customer segmentation analysis was not necessary or feasible given the client’s timeline, we still needed to gain an understanding of the key differences across those segments. By interviewing customers and several former general managers who led businesses in that adjacency, we were able to construct a view of the critical variances between segments in terms of competitor share and positioning, buyer values and preferences, and what it took to win.

| Key Outputs from Step 3: • In-depth assessment of market attractiveness and understanding of “what it takes to win” for each priority adjacency • Perspectives on how likely the company is to succeed in each priority adjacency • Feasibility of acquiring companies operating in each priority adjacency • Plan of action |

Armed with the “facts” collected through these in-depth research activities, a company will be able to answer many, if not all, of the important questions through sound analysis and synthesis. At the conclusion of this effort, leaders will have well-informed perspectives about which adjacencies make the most sense to pursue and how to pursue them. From there, it should be a fairly straightforward exercise to determine which course of action to take and when. Sometimes, the findings that come out of this three-step process will inform a company’s longer-term business development and/or product development roadmap. In other cases, the findings will strongly make the case for the quick pursuit of a specific acquisition target. Regardless, by following the guidance in this paper, an organization’s leaders should have a clear direction for how to make a meaningful impact on growth through expansion beyond their core business.